Los Nukak Makú: Expulsados del paraíso

No poseen casi nada y, sin embargo, conocen la mayor de las riquezas: la libertad. Mientras nosotros acumulamos cosas, los Nukak solo tienen su conocimiento y lo que pueden cargar. Su verdadera fortuna es el arte de vivir en el bosque y cultivarlo sin destruirlo.

Los Nukak, que viven en la remota zona fronteriza entre Colombia y Brasil, son uno de los últimos pueblos nómadas de cazadores y recolectores del planeta. Recorren la selva, levantan campamentos temporales con hojas de palma, cazan, pescan y reconocen más de 300 especies comestibles. Su forma de vida es tan antigua como la humanidad misma. Hasta hace poco, llevaban una vida plena y dichosa. Hoy son un pueblo al borde del abismo, expulsado de su propio paraíso.

A la sombra del auge del caucho: el éxodo Nukak

Pero esta vida no terminó por decisión propia. A finales del siglo XIX, la demanda mundial de caucho se disparó. Lo que en Londres, Nueva York, Iquitos o Manaus se celebraba como un milagro económico, desató en el interior del Amazonas un infierno. Comerciantes armados y esclavistas irrumpieron en la selva, empujados por la codicia. Los pueblos indígenas fueron perseguidos, esclavizados y masacrados. Según estimaciones conservadoras, la era de la esclavización del caucho provocó la muerte de cientos de miles de indígenas.

En esa época de terror comenzó el primer éxodo de los antepasados de los Nukak actuales. Entonces todavía formaban parte del pueblo Kakua, que vivía más al norte, y fueron empujados por el miedo a internarse en la más profunda selva. Su huida hacia los pantanos y bosques del actual departamento del Guaviare no fue una migración: fue una desaparición.

Allí permanecieron invisibles durante casi un siglo, no solo para la sociedad nacional, sino incluso para los pueblos indígenas vecinos. Este aislamiento autoimpuesto fue su protección y su escudo. Les permitió conservar su cosmovisión, su estructura social y su conocimiento ancestral del bosque. Sin embargo, ni siquiera el bosque más denso permanece impenetrable para siempre.

El segundo éxodo: coca, guerra y el fin de la libertad

En los años ochenta la modernidad los alcanzó, de forma brutal y definitiva. Esta vez no llegaron los barones del caucho, sino los cultivos de coca, los grupos armados y los frentes de guerra. El conflicto por el narcotráfico convirtió su territorio en un campo de batalla.

Su bosque fue fragmentado, talado para abrir potreros y plantar palma aceitera ilegal. Lo que había resistido siglos se derrumbó en pocos años.

Comunidades indigenas enteras fueron desplazadas, forzadas a una vida ajena y hostil. Las consecuencias fueron devastadoras. Enfermedades como la malaria, contra las que no tenían defensas, diezmaron a la población. Su modo de vida nómada, que depende de corredores intactos de selva, se volvió imposible.

La extinción de un cosmos

Pero la pérdida no es solo física. Cuando un pueblo capaz de distinguir más de 300 especies de plantas comestibles, que conoce el lenguaje de los animales y el secreto de cada raíz, es expulsado de su bosque, no desaparece únicamente una comunidad. Se apaga un cosmos entero de conocimiento. Un archivo viviente, guardado no en libros, sino en cantos, relatos y movimientos aprendidos al recorrer la selva. Con cada anciano que muere sin transmitir su saber, se desvanece una forma única de comprender el mundo. Irrepetible.

Por qué su historia nos concierne a todos

Los Nukak Makú son hoy ambas cosas: prueba de la extraordinaria diversidad de la vida humana, y advertencia del costo de nuestro llamado desarrollo.

Mientras nosotros, en una interconexión total, perdemos el vínculo con la naturaleza, ellos encarnan una relación con la selva que ha crecido durante milenios. Una coexistencia orgánica con un conocimiento extraordinario de plantas, animales y estaciones.

Su historia no muestra cómo el progreso de una sociedad asimila a la otra; muestra el brutal choque de dos mundos, en el que uno aniquila violentamente al otro. Sobre todo, sin embargo, nos recuerda que el ‘paraíso’ no se pierde porque la gente viva de modo distinto, sino porque una forma de vida extermina a otra.

En armonía con el bosque: cultura y modo de vida Nukak

La vida cotidiana de los Nukak encarna eficiencia y sabiduría milenaria. Este conocimiento íntimo de su entorno es mucho más que habilidad práctica. El saber vivir con la naturaleza y la capacidad de comprenderla se fundamentan en una relación espiritual con ella, arraigada en su compleja cosmovisión y una mitología rica en símbolos. Estas permean su vida diaria y cada aspecto de su cultura.

Navegan por la selva tropical con una precisión que continúa impresionando a los etnólogos. Conocen una increíble variedad de plantas comestibles y especies de raíces, poseen un gran conocimiento en medicina natural, leen rastros de animales con asombrosa exactitud y conocen los patrones de migración de los animales. Además, son muy hábiles cazando con dardos de curare lanzados con cerbatanas —una alquimia precisa de cinco plantas que paraliza a la presa a 30 metros— y se mueven a través de matorrales aparentemente impenetrables como si fuera un jardín familiar.

Su profundo conocimiento de las plantas también lo aplican a la caza de peces: Tratan pequeños afluentes con savia vegetal aturdidora y así pescan para la comunidad. Paralelamente, cultivan deliberadamente palmerales de Buriti, Miriti y Açaí, que proporcionan frutas, fibras y bebidas fermentadas para las generaciones venideras, una forma ancestral de economía circular sostenible.

Vida en movimiento

Su vida social se organiza en pequeños grupos familiares móviles. A diferencia de muchos pueblos del Amazonas que viven a orillas de los ríos, los Nukak eligen deliberadamente el corazón mismo del bosque. Allí, en la profundidad de la selva, encuentran sus recursos y su seguridad.

Su existencia se caracteriza por el movimiento constante. Rara vez permanecen en un lugar por más de tres a cinco días. Esta movilidad extrema no es inquietud, sino sabiduría ecológica. Al seguir adelante antes de que los recursos se agoten, mantienen el equilibrio del bosque. El bosque se regenera detrás de ellos; apenas dejan rastros. Sus ligeras chozas de hojas de palma, donde viven, se construyen en horas y desaparecen sin dejar rastro después de solo unos días.

El arte de no poseer nada

Su modo de vida es una maestría de la movilidad. Todo lo que poseen debe poder cargarse sobre los hombros a través de la selva. Su hogar entero puede empacarse en cuestión de minutos: las hamacas trenzadas (su posesión más valiosa) se enrollan; las ollas de barro, herramientas y algunos objetos más se guardan en canastos tejidos a mano. Luego, el grupo continúa su camino.

Lo que desde fuera podría parecer austeridad, es en verdad la más alta forma de autonomía, para ellos, la esencia misma de la libertad. Ninguna acumulación, ningún lastre, ninguna dependencia de las cosas. Su riqueza no está en lo que llevan, sino en lo que saben.

Nómadas: cazadores y recolectores

Su dieta es de una diversidad impresionante: peces, animales silvestres, tortugas, decenas de frutas, nueces, larvas, miel silvestre. Es difícil imaginar una alimentación más sana y sostenible. Pero esto es solo una parte de su relación profunda con el bosque.

Los Nukak no son simples usuarios de la selva: son también sus moldeadores. Al abandonar un campamento, dejan semillas y restos orgánicos a propósito. Saben que de ellos brotarán los árboles frutales y plantas que prefieren. Cuando regresan meses o años después, instalan sus campamentos junto a esos «huertos del bosque», no sobre ellos. Así, la cosecha queda intacta para la próxima visita.

Esta práctica va mucho más allá de la recolección: es una forma de manejo sostenible del ecosistema, perfeccionada a lo largo de milenios. La selva por la que los Nukak transitan no es virgen, sino un paisaje modelado por generaciones de interacción sabia. Sus huellas son semillas, y sus campamentos, con el tiempo, se transforman en huertos frutales.

Una tradición de nueve mil años

Las raíces de este modo de vida se hunden profundamente en el tiempo.

En el sitio arqueológico de Peña Roja, a orillas del río Caquetá (uno de los principales afluentes del Amazonas en Colombia), los arqueólogos encontraron evidencias de comunidades de cazadores y recolectores que habitaron allí hacia el año 7000 a. C. Este lugar se encuentra cerca de la región donde hoy viven los pueblos makú.

Además de herramientas de piedra, los investigadores hallaron miles de semillas de palmas aún comunes en la actualidad: burití, mirití, bacaba, açaí. Estos vestigios, con más de nueve mil años de antigüedad, demuestran no solo el uso de esas especies, sino su propagación y manejo intencionado. Las personas modificaban la composición del bosque de forma sistemática. Lo que hoy percibimos como una «dominancia natural» de palmas es, en muchos casos, una creación humana.

La continuidad resulta asombrosa: las mismas técnicas, la misma inteligencia ecológica, la misma movilidad, a lo largo de nueve milenios. La cultura Nukak no es un vestigio primitivo, sino un testimonio viviente de una de las adaptaciones más exitosas al bosque tropical que la humanidad haya desarrollado jamás.

Mientras nuestros sistemas agrícolas en la Amazonía agotan el suelo en pocas décadas y dejan tras de sí paisajes empobrecidos, los Nukak han creado un sistema que regenera el bosque desde hace milenios en lugar de destruirlo.

Englisch:

El mito del bosque «virgen»

La expresión «bosque virgen» revela un error profundo. La idea de que la Amazonia es una extensión infinita, verde y deshabitada, una tierra que espera ser conquistada, es un mito. Esta mirada no solo es falsa, sino que borra la verdadera historia de todo un continente.

El Amazonas nunca fue un territorio vacío. Durante miles de años fue un paisaje modelado y custodiado por pueblos indígenas. Mucho antes de la colonización europea existieron allí sociedades organizadas, que no devastaban el bosque, sino que lo transformaban en un hogar productivo: con redes de asentamientos, obras de tierra y un asombroso conocimiento de manejo sostenible.

Las huellas arqueológicas hablan de ese otro mundo: geoglifos, ruinas de antiguas ciudades y suelos de Terra Preta, en lugares que alguna vez albergaron a decenas de miles de personas.La inmensa diversidad biocultural del Amazonas, expresada hoy en más de 200 lenguas indígenas, no es un telón de fondo: es la fuerza vital de todo el ecosistema.La variedad actual de plantas cultivadas es herencia directa del trabajo de pueblos que construyeron el bosque con sus manos y memoria. Conservar la Amazonia significa proteger a sus habitantes.

Implica respaldar a las comunidades que han vivido allí durante incontables generaciones, sus mejores guardianes del equilibrio natural. Su conocimiento es nuestro norte en la crisis ecológica: son ellos quienes leen y hablan el lenguaje del bosque, los coautores de su pasado y la clave de su futuro. Ellos son el bosque.

La bendición de la palma

Para sociedades de cazadores y recolectores como los antepasados de los Nukak, las palmas no son simples fuentes de alimento: son sistemas completos de abastecimiento.

La majestuosa palma de burití es un sistema de recursos versátil: frutos nutritivos, un corazón rico en almidón, hojas para techos, vainas fibrosas para hacer cuerdas y «corchos» para recipientes de bebida. De su savia se prepara una bebida fermentada, y sus troncos ligeros sirven como balsas. Un solo árbol, docenas de usos.

La espinosa palma tucumá (Astrocaryum aculeatum) es quizá aún más extraordinaria. Su tronco entero está cubierto de largas espinas, como de puercoespín, que la protegen de los depredadores. Pero en el conocimiento indígena esto no es una barrera, sino una oportunidad.

De sus fibras se fabrican las hamacas y cuerdas más resistentes del Amazonas. Las temidas espinas mismas se transforman en clavos, agujas y herramientas. Sus frutos anaranjados son excelentes carnadas para la pesca, y su madera, altamente valorada en la construcción. Incluso un árbol «armado» se aprovecha por completo.

Açaí, sostenibilidad y el saber ecológico de los Nukak

Mientras la palma de açaí (Euterpe precatoria) es hoy celebrada globalmente como un «superalimento», para los pueblos del Amazonas ha sido desde hace milenios un pilar esencial de la vida. En la isla de Marajó y en todo el gran delta amazónico, los racimos de frutos violáceos, pequeños como arándanos, forman parte cotidiana de la dieta. El jugo o pulpa de açaí, denso y nutritivo, constituye, junto con el pescado y la yuca, una de las bases alimentarias de la región.

Los estudios modernos confirman lo que las comunidades amazónicas siempre supieron: el açaí es uno de los alimentos más ricos en nutrientes naturales del planeta, cargado de antioxidantes, ácidos grasos esenciales y vitaminas. Lo que para los pueblos locales ha sido desde siempre comida cotidiana, hoy el mundo reconoce como una fuente excepcional de energía y salud.

Para comunidades como los Nukak, el valor del açaí va mucho más allá de la nutrición. Su existencia misma encarna la sostenibilidad practicada: un estilo de vida nómada, un conocimiento preciso de los equilibrios ecológicos y una huella mínima sobre el entorno. Este saber tradicional, perfeccionado durante generaciones, revela que los Nukak no solo usan el bosque: lo modelan, lo cultivan y lo regeneran. Su manejo intencional de los palmares es prueba de una inteligencia ecológica milenaria.

Del paraiso al asilo

La catástrofe comenzó en la década de 1980. Impulsada por el auge de los precios internacionales de la hoja de coca, una ola de colonización avanzó sobre la frontera noroccidental del territorio Nukak. Miles de colonos, especuladores y aventureros llegaron a la región. El crimen organizado aprovechó la ausencia total del Estado: entró, arrasó el bosque e impuso su propia ley. Las comunidades indígenas fueron expulsadas violentamente de sus tierras y luego obligadas a trabajar como mano de obra barata en los mismos campos que les habían sido arrebatados.

Para los Nukak, la violencia se agravó con el conflicto armado entre las fuerzas del gobierno y la guerrilla de las FARC. Su territorio ancestral se convirtió en un campo de guerra. Atrapados en medio del fuego cruzado, golpeados por ambos bandos, su vida en la selva se volvió imposible. Muchos huyeron hacia un mundo desconocido.

Hoy, la presencia constante de grupos armados y redes criminales bloquea cualquier intento de retorno. Lo que alguna vez fue un espacio seguro y sagrado, es ahora una zona de peligro permanente. Aun así, los Nukak resisten: se reúnen para realizar sus rituales, entonar sus cantos y mantener viva su identidad frente a la amenaza del olvido.

La vida en el exilio está marcada por la escasez. La falta de alimentos es crónica; los recursos naturales de su territorio reducido ya no alcanzan. El trabajo forzado en las plantaciones de coca, sumado a las enfermedades introducidas (como la malaria), ha agotado física y espiritualmente a la comunidad, empujándola al límite del colapso colectivo.

El precio mortal del contacto

El primer encuentro con el mundo moderno pareció, al principio, inofensivo; casi una curiosidad. En abril de 1987 un grupo de Nukak apareció en el pueblo agrícola de Calamar. La noticia se difundió rápidamente y se convirtió en una sensación nacional. Pero lo que comenzó como un hecho anecdótico marcó el inicio de una tragedia. Con la expansión incontrolable de los colonos, los siguientes encuentros fueron inevitables y mortales.

El costo fue devastador. Los Nukak no tenían inmunidad frente a enfermedades traídas del exterior, como la gripe y el sarampión. La malaria, sobre todo, arrasó entre ellos: en pocos años su población se redujo casi a la mitad.

Más de dos décadas después de su desplazamiento, muchos Nukak continúan viviendo en condiciones precarias, dependiendo de ayudas humanitarias esporádicas, marcados por la escasez y el desarraigo. Su dieta, antes diversa y rica en recursos, se ha reducido a una amarga carencia. Un símbolo de esa pobreza: un solo pollo compartido entre veinte personas.

En 2006, su líder Mao-be se quitó la vida con el veneno vegetal tradicional de su pueblo, un último, desesperado acto de impotencia. Según relatan sus allegados, lo hizo por vergüenza de no haber podido proteger a su comunidad de la destrucción.

Hoy, los Nukak viven en asentamientos improvisados a las afueras de ciudades como San José del Guaviare, tras huir del caos que devastó su territorio. En ese limbo forzado, sin certeza de retorno, mantienen viva su memoria, sus cantos y sus rituales: un silencioso y digno esfuerzo por la supervivencia cultural.

De la vida nómada al campo de refugiados

Treinta años después de su reconocimiento oficial por parte del Estado colombiano, los Nukak viven una existencia fracturada. El cambio ha sido dramático: solo un pequeño grupo, en el extremo oriental de su territorio original, mantiene aún un modo de vida nómada. La mayoría se ha visto obligada a asentarse, viviendo en casas sencillas y cultivando pequeñas parcelas en los márgenes de las zonas colonizadas, territorios hoy dominados por la producción ilegal de coca.

De cazadores y recolectores se han convertido, con frecuencia, en jornaleros de estas plantaciones. El arte de cazar y recolectar, base de su identidad, se desvanece lentamente. Los Nukak figuran hoy, junto con al menos 32 pueblos indígenas de Colombia, como los más amenazados de extinción, entre ellos los Wachina y los Wipiwi. Un rayo de esperanza permanece en su territorio legalmente reconocido, ampliado en 1997 a más de un millón de hectáreas gracias a la presión de organizaciones como ONIC y Survival International.

Sin embargo, ese territorio protegido existe casi solo en el papel: cada día es invadido por colonos y grupos armados.

El anhelo del regreso

Su lucha central y más profunda es la del retorno: volver a los bosques remotos donde alguna vez cazaban y pescaban; volver a esos campamentos que eran como huertos silvestres, donde cultivaban palmas de chontaduro, ajíes, ñames y batatas, auténticos reservorios de su conocimiento.

En ese mundo no había lugar para los monocultivos de palma aceitera, ni para los pastizales de ganado o las plantaciones de coca.

Su destino, nuestro legado

Los Nukak encarnan una relación con la selva amazónica basada en una experiencia que se remonta a milenios. Su conocimiento sobre el uso sostenible de los recursos, la regeneración del bosque y los ciclos ecológicos es de un valor incalculable en tiempos de crisis ambiental.

Su historia revela las consecuencias devastadoras de un modelo económico que antepone el beneficio inmediato a la integridad duradera de los ecosistemas y las culturas. El Amazonas vive hoy bajo una amenaza sin precedentes: comunidades ancestrales son desarraigadas y empujadas al borde de la desaparición.

La pregunta crucial no es si admiramos a los Nukak, sino si tendremos el valor de proteger activamente el entramado de vida y conocimiento que ellos representan. En su destino se refleja nuestro propio futuro.

Para unos, el bosque es un ser vivo: un cosmos que respira lleno de espiritualidad y sentido.

Para otros, no es más que una mercancía, un almacén de madera, soya, petróleo y oro.

Entre estos mundos se abre un abismo más profundo que cualquier conflicto,

tan fundamental como el contraste entre la creación y la aniquilación,

tan silencioso y ominoso como el instante entre una oración y una sentencia de muerte.

Author Rolf Friberg

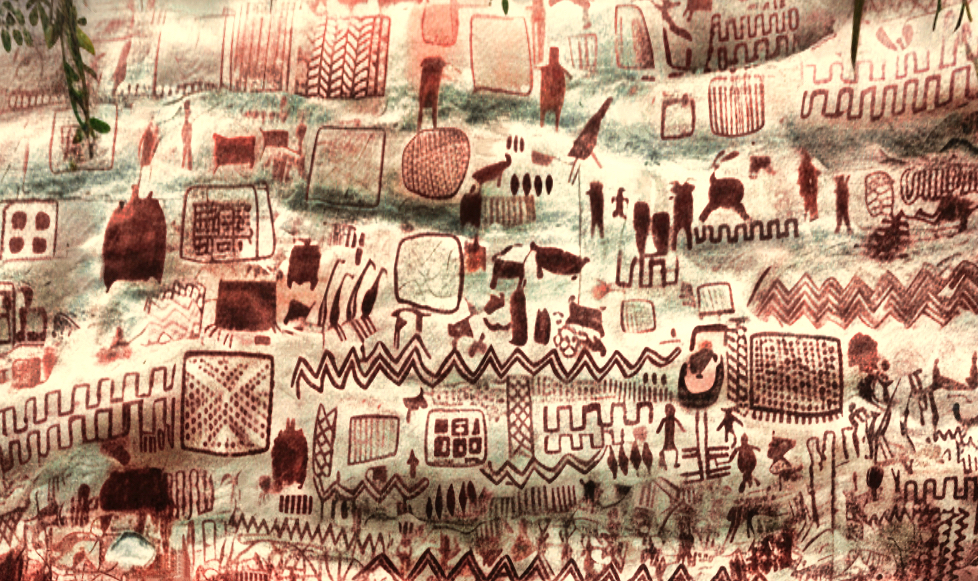

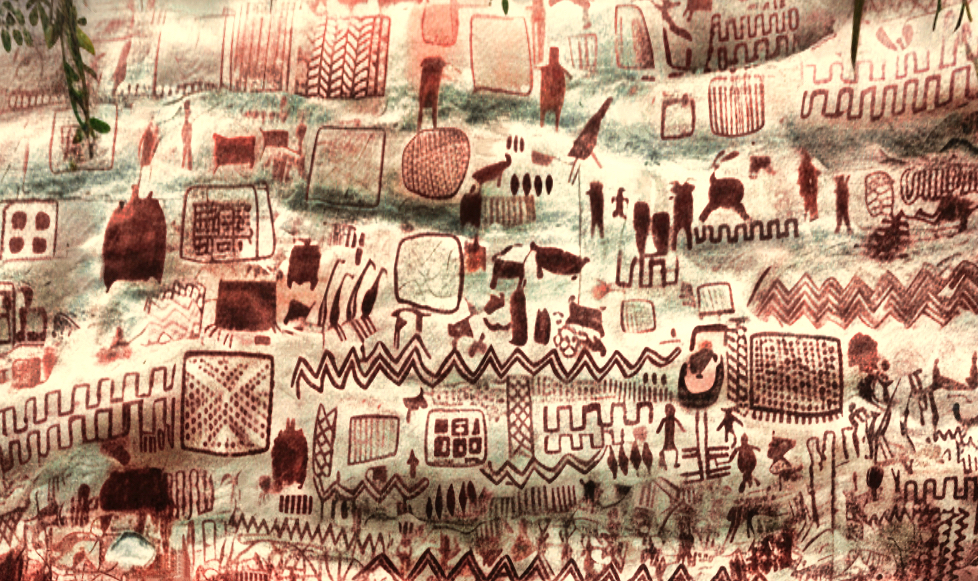

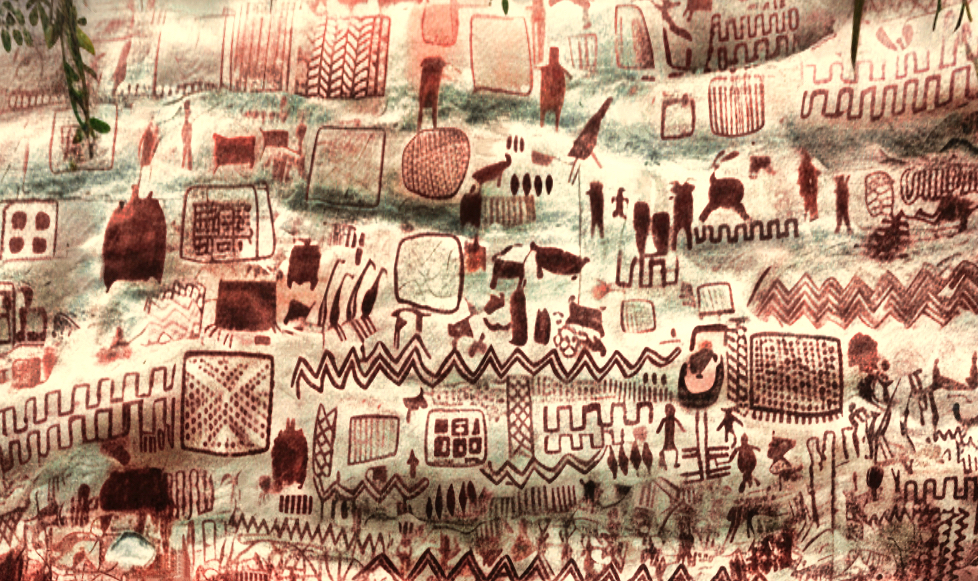

Chiribiquete, Arte Rupestre del Amazonas

Chiribiquete, un centro espiritual en el Amazonas, donde el arte rupestre ancestral guarda uno de los mayores enigmas de la humanidad.

Chiribiquete, Arte Rupestre del Amazonas

Chiribiquete, un centro espiritual en el Amazonas, donde el arte rupestre ancestral guarda uno de los mayores enigmas de la humanidad.

Chiribiquete, Arte Rupestre del Amazonas

Chiribiquete, un centro espiritual en el Amazonas, donde el arte rupestre ancestral guarda uno de los mayores enigmas de la humanidad.

0 comentarios