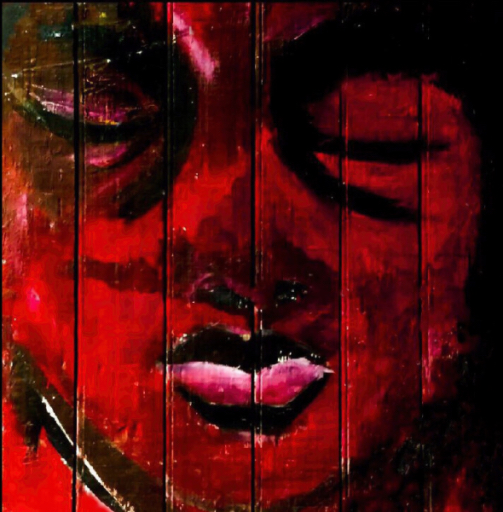

Santiago Yahuarcani. A visionary face emerges from a night sky woven with stars — a spirit figure where memory, cosmos, and ancestral presence meet.

Contemporary Indigenous Art of the Amazon

A Journey through Modern Uitoto Visual Culture

Custodians of Uitoto Memory—New Visual Horizons

A multitude of voices shapes contemporary indigenous art. Some artists stand out in particular because they have had a decisive influence on its development: the visionary power of Víctor Churay, the creative depth of Santiago Yahuarcani, the poetic universe of Rember Yahuarcani, and the mythical visual language of Brus Rubio.

Pulse of the Soul — The Power of Indigenous Art

These works serve a far deeper function than merely being decorative or museum objects. They preserve the collective memory, carry on spiritual traditions, and open up paths of healing from the scars of colonial trauma and the consequences of social injustices.

In this way, they give a voice to those who protect the rainforest, resist displacement, and stand up for their right to their ancestral home. More than artistic expression, they are a pulse beating from the soul of a people, and they carry the heartbeat of its unbroken vitality.

With their unique approaches and a deeply moving visual language, these artists have played a decisive role in shaping contemporary indigenous art to this day. Evolving from tradition, it remains powerfully present and of enduring relevance.

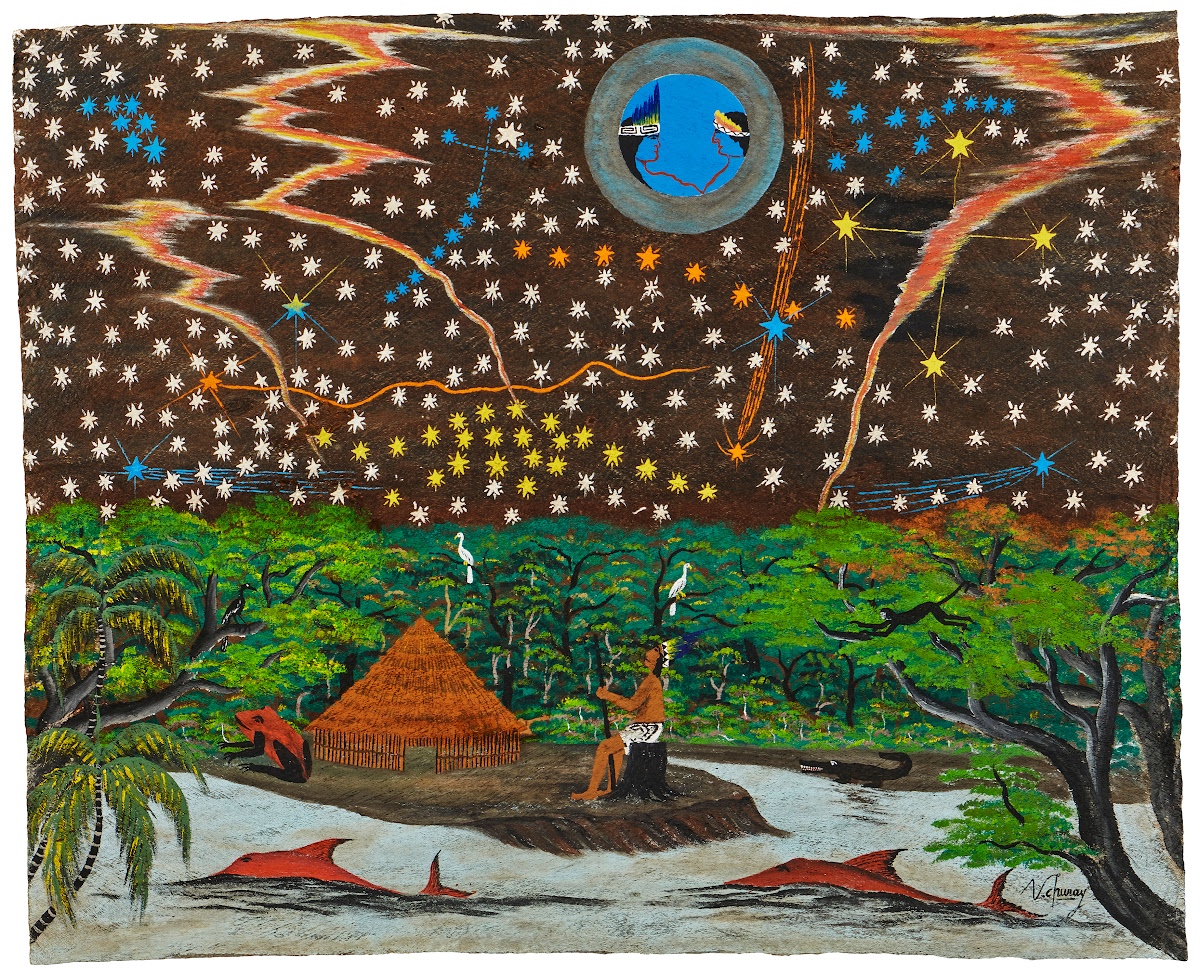

Víctor Churay Roque, Mapa del Cielo Bora. A man sits by the river, listening to the sounds of the forest and gazing up at the heavens. Stars, rivers, and spirits form a map that connects sky, earth, and memory.

Renowned Artist of the Huitoto People

Víctor Churay Roque – Ivá Wajyamu

“I don’t paint what I see, but what I feel. What comes to me in dreams, or what the ancestors show me. The images don’t come from me – they come through me.”

Víctor Churay Roque, also known as Ivá Wajyamu (“the one who comes with the word”), was an exceptional Indigenous artist of the Huitoto people who gained international recognition in the 1990s.

He is considered a pioneer of a new generation of indigenous artists who succeeded in renewing traditional indigenous art and connecting ancestral worldviews with contemporary forms of expression.

His artistic inspiration came from the wisdom of his ancestors, which was primarily passed on to him by his maternal grandfather, a Huitoto elder and guardian of traditional lore.

Through this family connection, Víctor received ancestral knowledge and was initiated into rituals with plants of spiritual significance. In his painting, this horizon of experience condenses into visionary worlds, where myths, spiritual beings, healing powers, and soul journeys take shape within a shared visual language.

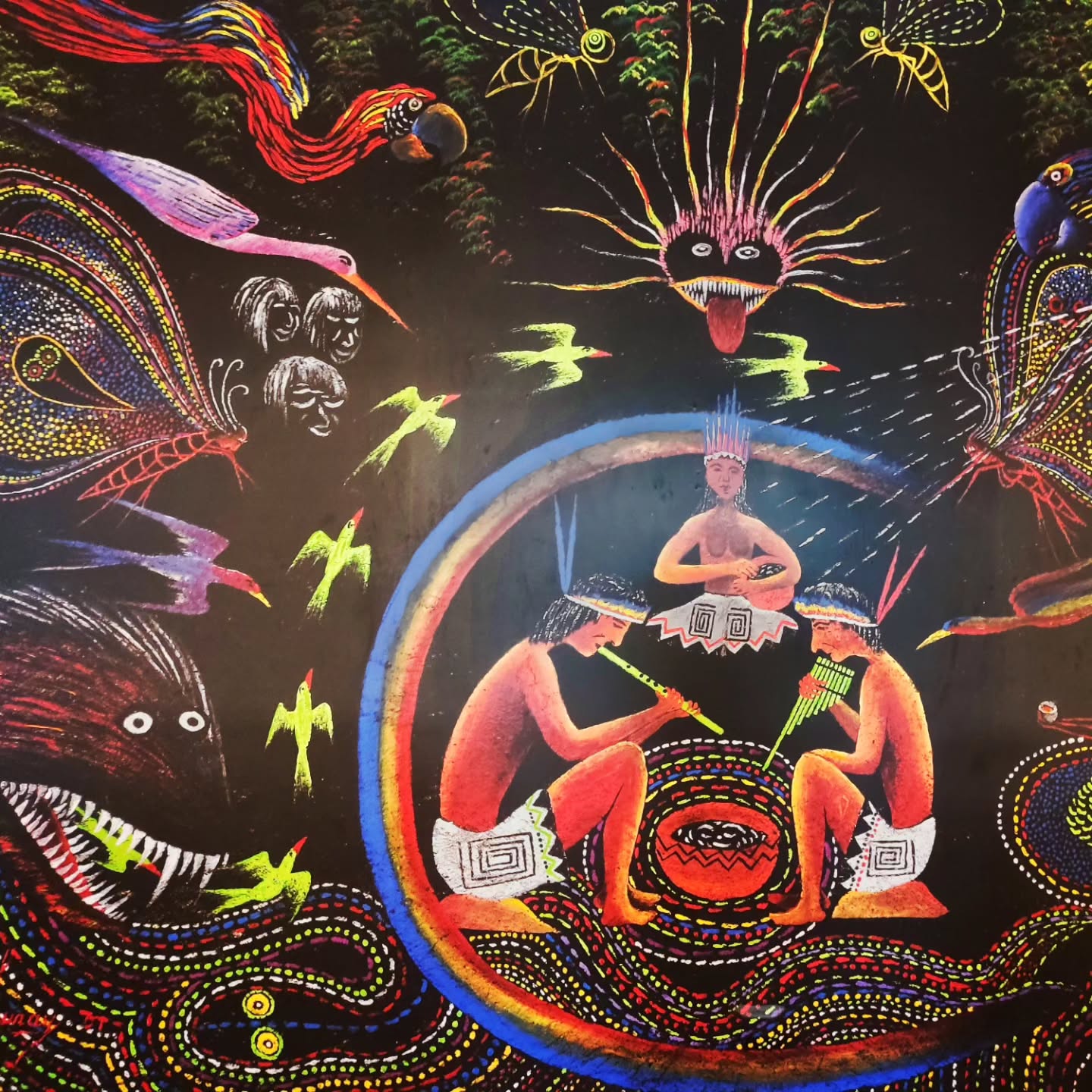

“Víctor Churay Roque paints a vision of music, ritual, and spirit. Flutes call forth birds, colors, and ancestral beings—where sound becomes light, and tradition turns into a living cosmos.”

A Pioneer of Contemporary Indigenous Art

Ivá Wajyamu was the first indigenous artist to move beyond local borders and exhibit his work internationally.

He presented his paintings in cities like Bogotá, Paris, and Havana, paving the way for many artists from the region. He made it clear that indigenous art does not have to be solely preserved but can evolve and assert itself as a critical voice of the present.

His art was not created in a studio—it came from the jungle. It grew from the heart of his community and the living memory of his people.

The paintings are not mere illustrations of ancestral myths, but a visible cosmovision —a response to cultural colonization and an artistic reclamation of his own history. Topics such as environmental threats and questions of indigenous identity also found their way into his painting.

In an interview, he stated that his art was a means of “turning his inner self outward.” For him, painting was both a form of healing and a cultural affirmation of existence itself.

Ivá Wajyamu died in 2002 under tragic circumstances, leaving behind a remarkable artistic legacy that remains of lasting importance to this day.

Ancestral Voices

Echoes of the Past — Shape of the Future

Santiago Yahuarcani

As an artist, the voice of his people, and a guardian of cultural memory, Santiago Yahuarcani is not only a pioneer of contemporary Indigenous art but remains one of its driving forces to this day. In his work, he forges a visual language that is at once political, poetic, and deeply spiritual.

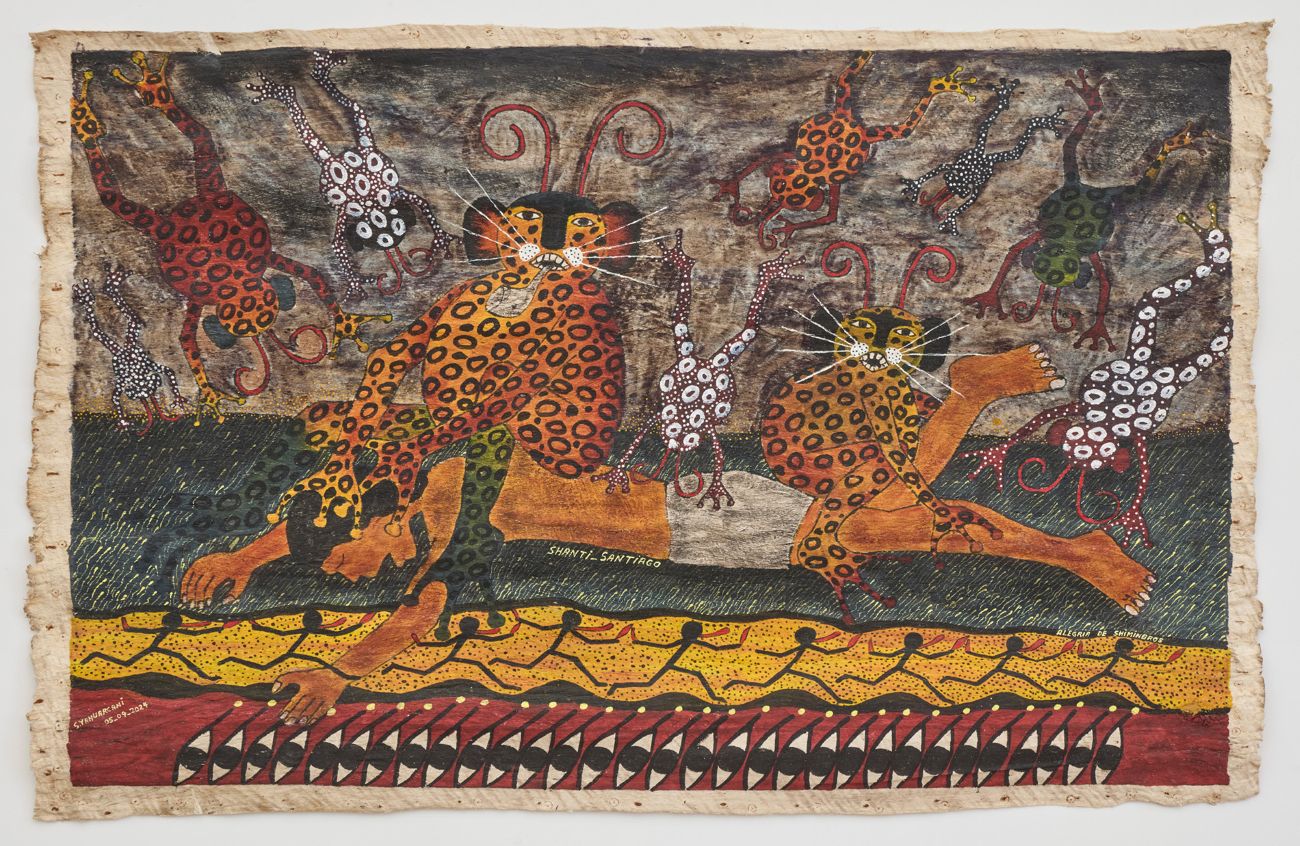

Santiago Yahuarcani — Alegría de Shimimbros (2024). A work that offers a glimpse of the rich spiritual universe of the Uitoto people.

“There is a world different from the Western one, still waiting to be explored. It is only just being discovered… Hopefully, we will still have time to share it.”

The Living Map of the Soul

Santiago’s paintings are both a testament and a renewal. They tell of displacement, colonial trauma, and the loss of land and culture—and at the same time, of what endures and is constantly reborn.

A steady stream of images unfolds, moving between grief and hope, between dream and history. Thus, Yahuarcani’s works become a living map of the soul. They invite us to recognize the inner connection that links the past and future, humanity and nature.

His art creates a space where memory and vision flow into one another, giving rise to a dialogue that both connects and challenges us. It urges us to question our way of life and our future, and to listen to the voices of those living in harmony with nature.

It reminds us of the importance of respectful coexistence and the preservation of the world we share.

Ultimately, his art honors the unbreakable resilience of the human spirit in a fractured world.

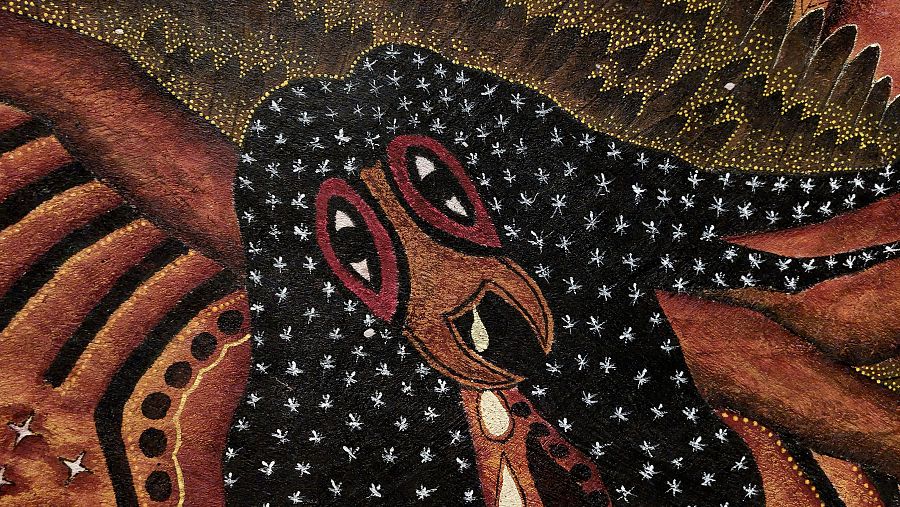

In this work by Santiago Yahuarcani, two figures are bound by flowing lines, while above them a female form transforms into a river. Lines and shapes open a view into a mythological realm where spiritual beings and cosmos come alive.

From Oral Tradition to Contemporary Indigenous Art

Beyond visual language, Santiago Yahuarcani forges an essential bridge between oral tradition and contemporary art. His works have been shown internationally in major museums and at renowned biennials, always accompanied by the voice of his community.

The Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI), Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid, MoMA in New York, Tate Gallery in London, MASP in São Paulo, and the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, as well as at the Biennale di Venezia, the Gwangju Biennale (2023), the Toronto Biennial of Art, and the Mercosur Biennale. Spaces such as Kadist in Paris have also featured his art.

In these exhibitions, he does not merely represent his culture—he reclaims it, questions it, and redefines it, drawing on memory, lived experience, and his vision of the future.

Santiago Yahuarcani, Castigo del caucho, 2017. A haunting depiction of the Putumayo rubber boom atrocities,

The Voice of a People on the Global Stage

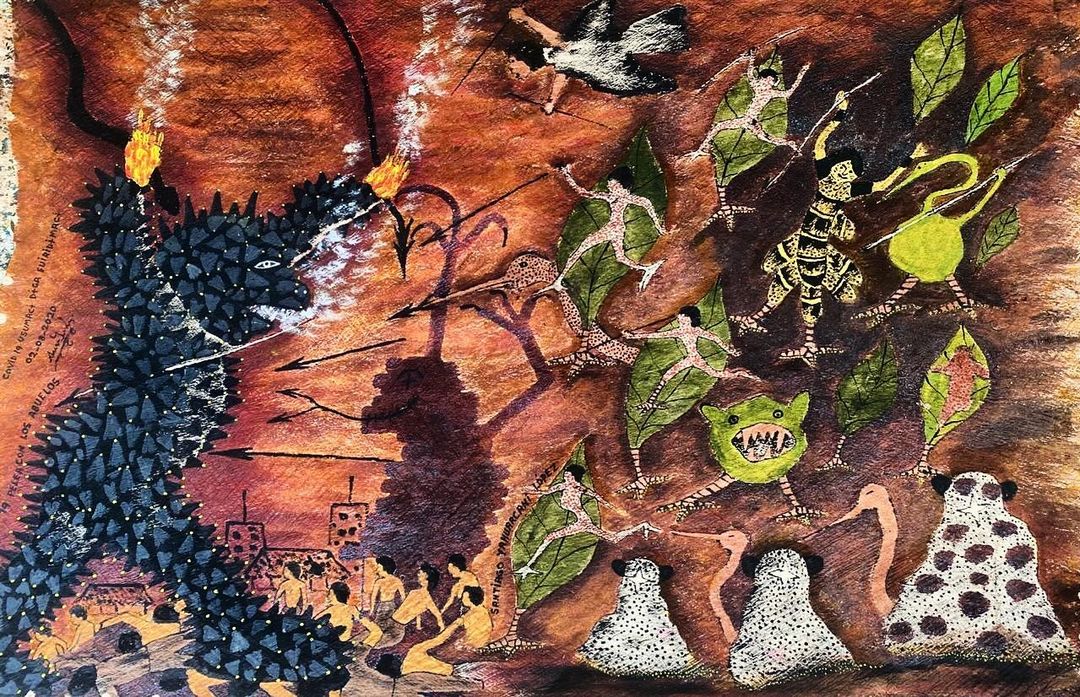

These works are more than aesthetic objects; they fulfill a deeper purpose. They carry on memory and spiritual traditions, opening a space for healing from the consequences of oppression and violence.

Santiago’s brush exposes colonialism, makes the voices of the ancestors audible, and honors those who protect the rainforest, resist displacement, and defend their land. His art is both an indictment and a powerful reminder—a moving plea for the dignity, recognition, and the right to self-determination of his people.

His works preserve the memory of the enslavement of the Uitoto people during the rubber boom (Putumayo genocide 1879–1912). This horror, which his grandparents themselves witnessed, has left a lasting impression that remains indelibly visible in his art to this day. It is both a tribute and a legacy that honors the suffering and dignity of the victims.

These images profoundly question our society by compelling us to face not only what is visible but also the shadows of a history that refuses to vanish. With uncompromising force, Santiago’s brush transforms silence into testimony, and memory into a living presence that challenges us here and now.

Santiago Yahuarcani, “Covid-19 Fights the Grandparents” (2020). Painted on llanchama bark, this allegory shows the clash between the dark force of Covid-19 and the ancestral strength of Indigenous grandparents, who confront the disease with spiritual power and traditional knowledge.

Art and New Horizons

Indigenous art shows that engaging with the past does not only bring painful memories or shameful insights, but can also be a source of change, reflection, and new horizons.

What moves us in it is not harmony, but truthfulness. Its expressive power and poetic force arise from spiritual depth, candor, and intensity.

This art recalls a repressed yet never-forgotten history of injustice while also revealing Western civilization’s profound alienation from nature. It relentlessly exposes the inhumane principles of the colonial past, showing how this heritage persists in our structures and mindsets, profoundly shaping our lives to this day.

The recognition of Indigenous art and thought as part of the global avant-garde opens a deeper understanding of this world — and of our role within it. In this dialogue, its power unfolds: not as a faint echo of the past, but as a living voice that invites us

to see, think, and act anew—and, ultimately, to encounter ourselves.

Part II examines the transformation of indigenous contemporary art and the role of art as a form of cultural resistance, its contemporary relevance, and its potential projection into the future. You can read it here:

Contemporary Indigenous Art Part II

This article corresponds to Part III of a three-part essay. You can find Part I here:

Contemporary Indigenous Art Part I