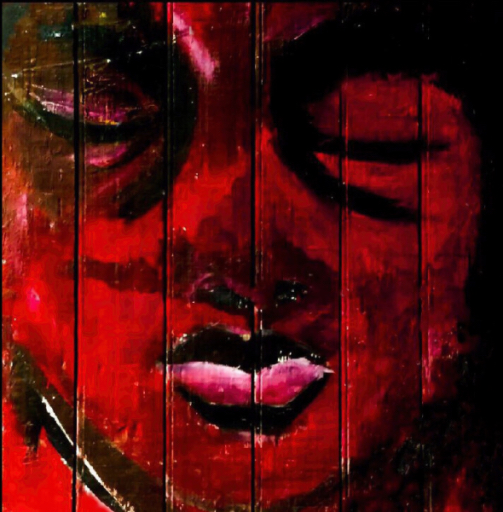

Brus Rubio, the spiritual guide, Indigenous Contemporary Art

Indigenous Cosmovision Ancestral Avant-Garde

A Blueprint for

Another Way of Being

The Cosmovision: Not an Image, but Its Breath

What we call a “worldview” is more than an outlook. For the peoples of the Amazon, it is a lived practice of belonging—one that could be called an Indigenous Cosmovision Ancestral Avant-garde. It carries the certainty that the human being is not the master of nature, but a relative among relatives. The jaguar, the river, the rainforest, and the starry sky are not resources or mere backdrops. They are persons with will, with history, and with voice.

In this way of seeing, there is no lifeless matter. Everything is animated, ensouled. A stone bears memory, a tree conveys messages, a river judges and gives life. This animistic attitude is not a primitive superstition, but a profound form of attentiveness. It demands respect in every gesture: one speaks a prayer before felling a tree; one gives thanks to the animal that offered its life for nourishment. It is an ethos of reciprocity—a continuous exchange of giving and receiving that keeps the web of life in balance.

Art as a Knot in the Web

The Indigenous Amazonian art you see here weaves within this web. It does not speak about connectedness—it ties it together. When a ceramic bowl takes the shape of a fish that merges into plant patterns, this is not ornamentation. It is the expression of a truth: everything transforms into everything else. The boundaries between species, between inside and outside, between bearer and carried, dissolve.

The recurring spiral motifs, the flowing lines—they do not depict objects but relationships and transitions. They show the world as a continuous act of birth, where death is not destruction but a necessary transformation. In these patterns, we are invited to question our own Western notion of time as a straight line from past to future. Here, time appears as a circle, a spiral—a constant flow of becoming and passing, in which everything participates.

The Mirror of Existence: Art as a Medium of Self-Recognition

When we allow ourselves to enter this way of seeing, something remarkable happens. The initial sense of strangeness fades. We begin to perceive the artwork not as an external object, but as a mirror reflecting our own, deeply forgotten sense of belonging.

Suddenly, our everyday experience of separation—between self and other, city and land, mind and body—no longer appears as a given, but as a form of cultural short-sightedness. The art allows us to sense that we, too, are knots within a much larger, living web. The breath we draw today once circulated through the leaves of the Amazon; the water within us once belonged to an ancient river.

In this moment, ecological consciousness is transformed. It ceases to be the guilty conscience of a proprietor who has neglected his garden and becomes the caring attentiveness of a family member toward an ailing relative. The destruction of the rainforest is then no longer a distant headline—it is the wounding of a kin.

An Invitation to See Anew

This art does not confront us with a demand; it offers a possibility. It invites us to momentarily set aside the lens of separation and to see the world as these cultures have experienced and lived it for millennia: as a sacred, sentient whole in which everything communicates with everything else.

At the end of our visit, we may take with us not only the memory of fascinating forms, but also a question: What might our lives, our economies, our sciences look like if we did not merely acknowledge this fundamental interconnectedness intellectually, but made it the very basis of our actions? The art provides no answer. Yet it holds the mirror in which we may glimpse the first, essential realization: we are not separate. We never were.

Brus Rubio, The Spiritual Guide: The Cosmos as a Living Organism

This work by Brus Rubio unfolds a world conceived as a living organism. The island of leaves, water, and bodies is not merely a setting, but a being that sustains its community. Human beings are not masters of nature, but a blossom growing from this body—protected, yet also responsible.

The spiritual guide who holds and propels the fabric of existence binds the levels together. In his form, animal, plant, human, and vessel merge into a single body. He is not an individual, but a movement—the force that allows knowledge, memories, and bodies to circulate between worlds.

The Threshold of Return

The painting proposes that nature, community, and spirituality are not separate spheres. The forest appears as the body, the rivers as veins, the community as the delicate blossom of the whole. Its message remains both simple and radical: whoever protects the forest protects the memory of the ancestors; whoever respects the rivers honours the body that sustains all life. In this sense, Amazonian art becomes an ancestral avant‑garde—a visual language that translates ancestral knowledge into a lucid, dense, and profoundly modern vision of the world as interconnectedness.

An Invitation into Another Order

When we turn to this depiction—not with the analytical gaze of the art historian, but with the patience of a guest beginning to hear a foreign language—something remarkable occurs. The initial strangeness does not yield to familiarity, but to a sense of being invited into another order.

We begin to feel how the fixed categories of our reality lose their validity here. The spiritual guide is neither animal nor plant nor machine, but the living breath of the forest itself. The community on his shoulder is not a village apart from nature, but its ripest fruit. The man who smokes is not an individual consuming a plant; he is the node where human ritual knowledge and the “spirit of tobacco” interpenetrate.

The Logic of Boundaries

In this order, boundaries blur not from lack of precision, but because they are drawn according to a different principle. Not between subject and object, between animate and inanimate, but between various manifestations of one and the same ensouled reality—as suggested by the circulating waters and beings within the painting. The river on the island, the sea below, and the rain that may fall from the gate are not distinct elements, but different modes of existence of the same sacred water of life.

A World Full of Life and Answers

What appears here is not a portrayal of nature, but the emergence of an animated world—a world in which everything—the stone, the tree, the river, the ancestor at the gate—possesses intention and voice. A world not composed of dead matter that humanity must enliven, but one already full of life, offering answers to those who are willing to listen.

The Existential Reflection: When the Image Begins to Look Back at Us

This sensation is more than an aesthetic impression; it is an existential reflection. Suddenly, the world we habitually inhabit—a world defined by strict separations between self and environment, mind and body, sacred and profane—no longer appears self-evident, but as a particular, perhaps even limited, way of perception.

The painting does not pose a question to be answered by reason. It addresses our entire mode of existence: What might change if we perceived our reality not as an assemblage of separate objects, but as a living, communicating web? If we understood the forest not as a resource, but as a relative; the river not as a watercourse, but as a teacher?

In the stillness before this image, for a fleeting moment, this other order can be not only conceived but felt. And in this sensing lies the first seed of a transformation in how we relate to the world.

An Invitation into Another Skin

This contemplation does not leave us untouched. It quietly, yet inevitably, poses the question: what happens within us when we allow this non-dual way of seeing—even if only for the duration of a single breath before the painting?

It is as if, for a moment, we were to slip into another skin. The skin of separation, which makes us appear as isolated individuals in a world of objects, becomes permeable. Our own being no longer feels like a point set against the world, but like a pulse within it.

The breath we draw seems to be the same current moving through the foliage of the guide; the body ceases to be a fortress and becomes a node in a web of relations—to nourishment, to water, to air, to history.

Symptoms of the Dividing Gaze

Thus, a second question arises: Could this perspective be more than a fleeting aesthetic experience—perhaps a necessary corrective to our dividing worldview? Our modern world, shaped by efficiency, extraction, and the belief in human exclusivity, is built upon division: between subject and object, culture and nature, profit and cost. Ecological destruction, alienation, and loneliness are not accidents, but symptoms of this perception.

The Indigenous worldview, as this painting breathes it, offers no technical remedy. It offers something more fundamental: a model of perception in which healing and destruction are inwardly felt. If the river is a relative, its poisoning is my poisoning. If the forest is the body that carries me, its deforestation is an amputation.

Practicing Connectedness

The corrective lies not in a new ideology, but in a new sensibility. It is the cultivation of perception that experiences connectedness not as a concept, but as a bodily certainty. The challenge posed by this painting is therefore not archaeological—“this is how other people once thought”—but immediate: can we learn, at least in moments, to step out of the skin of separation and slip into the skin of connectedness?

The painting offers no answer. Yet it holds up the mirror of a possibility. It invites us to question the most fundamental assumption—that we are separate. From this single openness, everything else may unfold: more responsible action, and a deeper respect for the world, for others, and for ourselves.

Epilogue: The Space as Beginning

At the end of this reflection, there is no conclusion—only a return to the beginning: to the painting, to the space surrounding it, and to the quiet challenge that emanates from it. Through such a reading, this gallery is transformed. It is no longer an archive of completed worlds, but an entryway into an ongoing question.

The conceptual approach—the interpretation of the spiritual guide, the tracing of cosmic breath, the translation of pattern into meaning—has not aimed to explain a work, but to uncover a way of seeing: one that perceives, in the flowing unity of human, animal, plant, and spirit, not composite appearances but a shared foundation of the living world. In the procession toward the gate, it does not recognize a distant mythology, but a functioning cycle: all that is given is returned, transformed, and poured out anew.

As this essay draws to a close, the true work begins with the viewer. It lies not in reading further, but in seeing differently. The works gathered here—above all, that of the Spiritual Guide—are then no longer objects of analysis, but occasions for contemplation. They invite us to suspend, if only for a moment, the habitual perception that situates us as separate subjects in a lifeless world. They offer a provisional home within another order—one in which connectedness is not an abstract ideal, but the tangible ground of all being.

The Gallery as a Space of Practice

The gallery thus becomes a space of practice for attentiveness. Each painting is a small lesson in non‑dual seeing, each pattern an exercise in perceiving relationship before separation. It is a practice of great urgency, for the crises of our time are, at their core, expressions of a destructive separation—the separation of humanity from the web that nourishes and sustains it.

The way out of this error lies not in more technology or information, but in the re‑learning of perception. Amazonian art, as it appears here, does more than preserve cultural memory; it offers a practiced way of perceiving—an outline of how a society might understand itself as an inseparable part of a living whole.

The Art Looks Back at Us

This essay, therefore, ends with a reversal: it is not we who look at the art, the art looks at us. It asks whether we are ready to break through the illusion of separateness, whether we dare to perceive ourselves, if only in the act of looking, as part of that community upon the island of plants: sheltered, sustained, and jointly responsible for the great breathing being that carries us.

The answer does not lie in these pages. It begins in the moment we lift our eyes from the page and, seeing anew, meet the painting, and the world, once more.